Shirley Leon: BEd’87

This interview was originally posted on the Faculty of Education’s Year of Teacher Education website as part of the Inspiring Educators series.

Shirley Leon (Siyamtelot) grew up in the Okanagan community near Vernon, BC (née Shirley Marchand). Her ancestors are Okanagan and she lives in the Stό:lō nation with her husband, Rudy. This interview took place at UBC with Wendy Carr, Director of Teacher Education and was facilitated by Shirley’s granddaughter, Jessica La Rochelle, who is Assistant Director of UBC’s Indigenous Teacher Education program (NITEP), the program from which Shirley graduated in 1987.

Shirley Leon (Siyamtelot) grew up in the Okanagan community near Vernon, BC (née Shirley Marchand). Her ancestors are Okanagan and she lives in the Stό:lō nation with her husband, Rudy. This interview took place at UBC with Wendy Carr, Director of Teacher Education and was facilitated by Shirley’s granddaughter, Jessica La Rochelle, who is Assistant Director of UBC’s Indigenous Teacher Education program (NITEP), the program from which Shirley graduated in 1987.

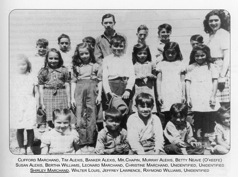

Shirley was the third youngest in a family of 13 in which no one had ever graduated from high school or university. Her younger sister left school in Grade 9 to go to a vocational school in Winnipeg to become a hairdresser. Later on she got certification as what is equivalent to an LPN today. The two oldest brothers enlisted in WWII and learned trades there. The youngest brother is a successful businessman. Her mother was illiterate and her father could read and write, but they stressed the importance of education and independence.

Going to School

Leaving the reserve was really unheard of during my childhood unless it was to go to residential schools, as our cousins did. This was really adventurous in those days, and those of us who weren’t allowed to go used to cry and want to go to residential school because they were meeting new people and telling us stories about people from all over the province. We didn’t have those kinds of experiences. I attended a federal day school that had very low standards and the teaching staff was really sporadic as it was difficult to get good teachers on an isolated reserve.

Right from the very beginning, I was always interested in learning and curious about everything. My generation was the first to integrate into the public school system. Before that we weren’t allowed to go into the public schools, and this was in 1952. So it was a real cultural shock because we all had long hair and braids and to go to the public school, our parents thought we had to get our hair cut and get perms. They loaded us on our neighbour’s cattle truck to Vernon to get our hair cut and get perms to fit in. We didn’t think we were beautiful at all coming home. We just wished we could scream our lungs out all the way home because we hated how we looked. And this was prep for going into public school. To me, it was kind of like a warning that it was not going to be a very nice experience.

After that first experience, I moved to Falkland, and the public school there was much better because it was smaller and it was more of a ranching community. We grew up on a ranch so we could identify more with other students. But I dropped out in Grade 9 and got married very young. Even so, somehow in the back of my mind, I always knew I was going to get an education and, because of the racism or denial of First Nations for such a long time, I had in my mind that someday people are going to meet me and they are going to know who I am and I was not going to be a government statistic.

Living in Agassiz

When I got married and started having a family, we bought a house in Agassiz. It was just an old shack and we fixed it all up and after about four children, we decided it was too small and we should buy a new house. We met a Dutch family who was building a house on Vimy Road and were willing to sell it to us. Then a petition got taken up by the community members to keep us from buying the home because they didn’t want their properties to be devalued. But thank God the Mayor and Council of the day discarded it; however, it left a mark. Everything was okay when the children were in elementary school, but when they got into high school, I noticed that they kept streamlining them into vocational programs and I didn’t want that. I wanted them to be in academic programs. So I started to learn what the system was all about and I started attending meetings of the first regional organization called the BC Native Indian Teacher Association. It started in University of Victoria and it was just prior to the infamous paper of Indian Control of Indian Education in 1973. From there the Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) was formed and they were really keen on looking at the quality and relevancy of education and using the Indian Control of Indian Education policy booklet.

I got involved with a committee of UBCIC to review the federal Master Tuition agreement in preparation for developing a regional education position for our children. I ran for a position on the Agassiz School Board in 1969. In those days, you had to get the signature of two people to run, so I went to the highest office, to the Mayor’s office and Chairman of the School Board to nominate me to run for Trustee. I won and I was very nervous but soon learned the board members were good people. They were all farming people and a couple of them were neighbours. They were real supportive mentors. The Secretary Treasurer was especially helpful; secretary treasurers are usually the backbone of school districts. I learned a lot about the system and how to play the game. The one I had to be on top of all of the time was the school counsellor. And at that time my daughter, Cheryl, was going into Grade 9 and wanted to go on the academic program, but he kept insisting she shouldn’t go on the academic stream. He often told me that no First Nation ever graduated on the academic program. And I said, “There is always a first time. Where there is a will, there is a way. And we want the way.” There is an important saying in my family: “In life, you reach for the top, not for the bottom of the barrel. And if you don’t make it, at least you know you’ve tried.”

Developing Culturally Relevant Curriculum Materials

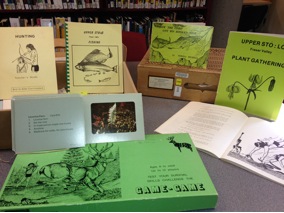

Sto:lo Sitel Social Studies Curriculum Resources (developed by Coqualeetza colleagues and coordinated by Shirley)

Because of my own life experience and my children’s, I decided to continue my work in education. I got involved with the Coqualeetza Cultural Education Centre established in 1973 at the direction of the members of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs. Together with Jo-ann Archibald, who was teaching in Chilliwack at that time (and one of the only Stó:lō individuals who graduated from UBC’s Teacher Education Program), we initiated a Social Studies curriculum because we knew that there had to be some relevant information in the schools to capture the attention of our children. When we went to school, there was nothing we could identify with. In Social Studies, I couldn’t stand the negativity about Indians, so we wanted to have culturally relevant materials. And we knew that you could teach the same learning outcomes by using information about Stό:lō or any other First Nation group in the province.

As we lobbied to have our curriculum accepted into the school districts, we also wanted it accepted by the Ministry of Education. At that time, there were calls going out for proposals for social studies, so we met with then premier, Eileen Daily and I learned that, without an education, you are nothing and nobody. I did my research, I read and studied everything. I was in constant contact with the Social Studies department here at UBC and they mentored our project. So I learned about curriculum development and how to write goals and objectives and lessons according to IRPs. School districts started to say, “Well, it’s not done by qualified people.” So I thought, “How am I going to be heard without certification?” I decided to go back to school and do the teacher education program, which I did part-time. By my last year, I was taking eight courses just so I could finish. I didn’t have time to waste. I had to get this done. I really wanted to have the curriculum validated so that there would be more relevant information in the school curricula. That’s how I got into teacher education.

Entering UBC’s Native Indian Teacher Education Program

I really liked NITEP because the practicum was up front. I wanted to know right away if I could do it, if I could handle a class. NITEP had a centre in Snookwa Hall on Coqualeetza property, Chilliwack, so the participants were my inspiration. First, I went to Fraser Valley College to get my GED. My daughter, Cheryl, and I graduated the same year. Then almost simultaneously, I started taking courses that were transferable to NITEP. I signed up in 1983, so I was a very mature student. I really enjoyed the support mechanism in NITEP and the accessibility to advisors. It gave us confidence. There were 15 of us in the group. One of the areas I knew I was weak in was Geography, so I took a lot of Geography courses, for example, Social Geography of BC, because that was my passion. You know, the most important thing in education is to have a teacher who is good at all aspects of teaching. And we wanted to get our students off of the reserve into the bigger world, so we had to know something about the world. That was what I knew I needed to motivate students. I finished the program in 1987 and got my BEd degree. My family was present when I crossed the stage and they were all crying. It was a glorious day.

I never had the intention of having a permanent classroom. My motivation was to foster changes in policy whereby recognition of the history of the first peoples would be acknowledged and learned about. That began with promoting culturally relevant materials and to set standards within our schools, especially in our own community schools. That’s what I devoted my life to, and I hope I was a small part of the effort in our own community school because I am so proud of what they do. They have such a challenging group of students. Personalities are flexible so they can make adjustments, for example, if there is a particular class that is just not into classroom seatwork, they can use the environment for Science or for Geography. Just recently, one of the alternate education programs learned that using drumming and singing was an effective way of getting the class together and more focussed, so they start the day with a drum song. Simple little things like that is what is necessary, especially in our communities.

Stό:lō Awards Ceremony (initiated by the curriculum project) Shirley Leon presents award to Kristopher Giroux

That is where I devoted my intention and energy—bringing more accessibility and more choices for our students so it’s not just a vocational path or a First Nations’ path. At one time, there were only two First Nations programs at UBC: NITEP and Law, so everybody who graduated signed up for NITEP or Law even though their passion might have been engineering or medicine. When my granddaughter, Jessica, got her Bachelor of Arts, there were over 10 different disciplines that students were acknowledged from. I was overwhelmed and actually cried to witness such growth. I was thinking that this is what NITEP did. The teacher education program started here in a little hut, one of those sea island huts—the ugliest looking building. I never thought that one day we would have graduates in all these programs. It was amazing. In my lifetime, I am witnessing this.

Working in Community Education

My newest passion is family tree research for First Nations adults who have been fostered or adopted and don’t know what their roots are. We are now just getting into using this research in addictions programs. I’ve gone to at least three different cultural areas and promoted it. It works wonders because I believe that in order to be successful, you have to feel good about yourself. And with all the publicity with residential schools, it doesn’t give us much to be proud of. When you set up the stations for family tree research and individuals find writings about their relatives in the newspaper or census report, it starts to build self-esteem. They start putting together their own albums with photos and documenting careers and experiences of different family members. A lot of our communities have a good collection of baskets and canoes so they can see the mastery it takes to achieve what has been left behind by their ancestors. Then pride starts to come and then self-confidence. Then they can make their choice to be whatever they want to be.

We have the Great Spirit on our team; for example, there were two young ladies: one worked for one of the CUPE offices in downtown Vancouver and the other one worked for Fraser Health Authority as a mental health worker on the streets. They were raised by foster parents and didn’t know who they were. Just by some miracle, we found their families. One was from Chehalis, our community, and one was from Seabird Island. We were able to introduce one of them to their families, and they had several family gatherings to get to know each other. It’s really emotional because there has to be a long term working out of why someone was abandoned or why he or she was given up to Child & Family Services, especially if the mother or a parent is still there. I tried to make it my business to know whom I can refer them so I am not just opening up a can of worms and leaving them there. It has been really rewarding and now one of my nieces met a lady just last week when she was getting her car serviced in Mission. The lady came up to her and said, “I know the owner of this dealer and he says you are native. Well, I am native too, but I never lived as a native.” And now she wants to find her roots. She is from Musqueam, where there are only 34 registered in the 1980 Indian Registry and only 5 in Vital Statistics, and the family she comes from is huge, so I have to rely on the Great Spirit to help me figure that one out.

A few final thoughts

My experience in NITEP and at UBC really affirmed what I always believed and also opened a lot of doors. I think for the first time I was able to witness the best of both worlds because of the people that I was fortunate to meet in the programs. We worked together as a real team, real equals. That’s what I’ve always appreciated from NITEP is seeing other people as equals whereas all my life I felt I wasn’t good enough and had to prove myself. I now have a great life and feel so blessed with my family and the support I get from them and seeing them as fulfilled individuals.